A few months ago, I was on a Microsoft Teams call. As one sometimes does to distract themselves from looking at their own face, I started clicking buttons around the Teams call window. I found an interesting one directing me to a “Speaker Coach”. Clicking on it, The AITM started listening to me talk during the call.

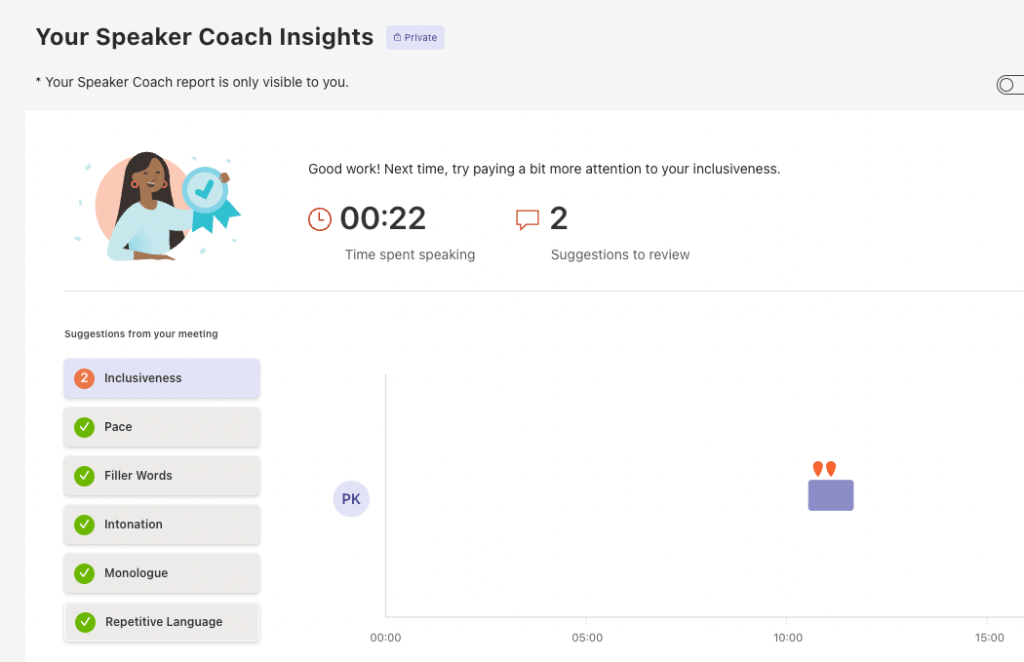

I can’t remember what we were discussing in the meeting, but I mentioned the word Toastmasters, referring to the public speaking organisation. A prompt appeared from the Speaker Coach telling me that the word “master” may be offensive to some and I should rather not use it. Amused at this, I tell the others in the meeting that the Teams Speaker Coach said I should not use the world Toastmasters because it has the word “master”. Again, the prompt from the speaker coach comes up. After a short time of this, I decide to stop this, and after which I received the report below:

I scored well on a number of metrics that are apparently important to proper speaking, but had some “room for improvement” for Inclusiveness, because of my use of the word “master”.

I can understand the why behind this. The trans-Atlantic slave trade and the slavery that the American society was built on was evil, subjugating and destroying the humanity of slaves by their masters, and robbing future generations of full personhood. These effects are still evident and at play today, with many organisations fighting to correct the injustices of the past so that, as Martin Luther King dreamt, “one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.”1 Yet, this is not everyone’s story.

Around the world, different historical events and movements have led to different localised cultural norms and values. Popular technology opinion maker David Heinemeier Hansson wrote about the differences between Danish and American society, where in America diversity is a highly-esteemed value, whereas in Denmark conformity is highly valued. I wrote about how using Uber in Kampala is very different to using Uber in Johannesburg or Paris. Yet, the digital platforms we use are built on historical presuppositions, values and cultural norms of those in San Francisco and Seattle, conforming all of us users to those norms.

What makes this trend irreversible is that most of the world’s communication goes through platforms and servers of companies in USA. Most communication around the world is done using WhatsApp, owned by Meta. Corporate communication is increasingly being done through platforms such as Microsoft Teams and Google Workspace as companies increasingly default to digital-first cultures. And the cultural presuppositions that these tools are built with are increasingly shaping the various cultures in which they are used.

In 1875, Ssekabaka Muteesa I, the King of Buganda sent a letter to Queen Victoria, the Queen of England, inviting missionaries into Buganda with the hope of increasing the kingdom’s economic position and military protection, as well as educate his populace in manufacturing, trade and medicine. After missionaries had come from both England and France, factions had formed, not based necessarily on local differences, but on power plays and conflicting values imported from the European nations. During the reign of Muteesa’s son, Ssekabaka Mwanga, a civil war broke out between these factions which ultimately led to the capture and deposition of the monarch and the kingdom’s loss of sovereignty.

History can guide us in the bargains we make today with foreign technology platforms for the sake of progress.

Photo by Kenny Eliason on Unsplash

- King, ML. (1963) I have a Dream ↩︎