Access to the world on one’s phone has provided possibilities and efficiencies that previous generations could never have dreamed of. Whether it’s bypassing traffic jams on the outskirts of hills of Kampala, or it’s determining your public transport route from your hotel to your tourist destination in the hills of Rome, an application like Google Maps has provided immense benefit to people around the world by centralising location and geographic data. Within one generation, many of those who live in cities around the world have come to hold these tools as indispensable.

Yet on the other hand, in providing magical efficiencies, they have taken away the unintended human benefits caused by the frictions of their alternatives. Before the advent of the music player, music was inherently communal. The producer and the consumer of music had to be co-located. Songs that were sung were limited by geography to the distances the musician could travel. A relationship of sorts could be formed between the musician and the hearer, and the listeners could communally enjoy with the opportunity to share their appreciation with each other and the musician, potentially igniting tangential sparks from the human interaction.

Today on the other hand, music is inherently individual. Driving in a car on a long journey, each person in the car can listen to their own playlist. With infinite choice from Spotify, one person in a family is not bound by another’s taste. Appreciation and commentary on the music is shared on online forums such as comments on YouTube videos. Yet, the avoidance of friction from a foreign taste has taken away the opportunity for others to potentially acquire that taste, and more importantly, the opportunity for others to know the beholder of that taste more. How did things change so much within a generation? Maybe, the foundation such a society was built on made this individualism natural.

The book of Judges in the Christian bible narrates the regression of the ancient federation of Israel, a federation of tribes formed along family lines. The book starts after the nation has reached the high point of their desires by resting in the land that was promised to them after over 400 years of slavery in Egypt. They have a good law by a loving God, as well as promises of flourishing if they choose to walk in the light of His instruction.

Narratives are beautiful porters of wisdom. Since the days of the enlightenment and its defiant progeny of modernism, codified human reason and logic has not been able to describe the human experience in its complexity. Abstract philosophical principles have been found wanting. Scientific reasoning has explained the heart in all its biological significance, while failing to adequately to describe the “why” and the “therefore” at the heart of it all.

Ancient cultures around the world have used stories to convey truths which have guided societies and civilisations. Proverbs and narrative retellings have been framed in such a way as to convey more than “facts”, but to convey “truth”. And much of this truth is only discovered through time of individual and communal meditation.

One tense strand of wisdom that has been conveyed by the book of Judges is the pitfall of a lack of a strong central authority within a nation. There is the constant refrain after each further descent into chaos: “In those days there was no king in Israel; everyone did whatever seemed right to him.” Temporary leaders – which the book calls judges – periodically ascend the social hierarchy and lead the nation during specific missions. Yet, the nation has no sustaining centralised human institutions that last over generations.

Many have seen this work itself out in rural areas which are far from the clutches of an efficient and centralised state. The prevalence of honour killings, large scale death through the destructive forces of nature such as natural disasters and pestilence, and limited opportunities to reach one’s potential show the shortcomings in the community’s attempts to subdue the earth. The community is subject to the unrestrained thorns and thistles of a fallen natural world, and the fallen human heart.

On the other hand, many such communities are governed by rhythms centred on human life. Weddings and funerals are multiple day affairs with meaningful rituals guiding communities into transition. Rites of passage give roles to members of a society, giving them a place and a purpose in the communities in which they live. And sub-communities of trust form as a safety net from which to navigate the forces of nature, and the dangers of fallen humanity.

Later in the biblical narrative, the books of Samuel narrate the rise of the kingdom of Israel, first under Saul and later under David. When the Israelites ask for a king, they are warned by the prophet Samuel that the king would “take your sons and put them to his use in his chariots… He can appoint them for his use as commanders of thousands or commanders of fifties, to plow his ground or reap his harvest, or to make his weapons of war and the equipment for his chariots.” The king, the strong central authority, will break apart the natural relationships of people for the flourishing of the central authority, and maybe the flourishing of the people as a by-product. This outworks itself during the rule of Solomon, David’s son, where he builds both the temple and his own palace. The kingdom reached the highest point of its glory with dignitaries from nations around the world coming to see it for themselves. Yet after his death, the people of Israel requested his son Rehoboam to give them reprieve from the subjugated labour, showing that this was all done at incredible social cost, just as Samuel had warned.

When entering the capitals of the so-called developed countries, one is struck in awe at how well everything runs. Trains and buses run regularly and on schedule. Public facilities such as schools and hospitals are available to their citizens. Jobs are available providing income to buy food for one’s family, food which is always available in the supermarket despite the thorns and thistles of nature such as drought and pestilence. It’s as if those who’ve built such societies with strong centralised authority have done well to subdue the earth, and have subdued humans as part of the project.

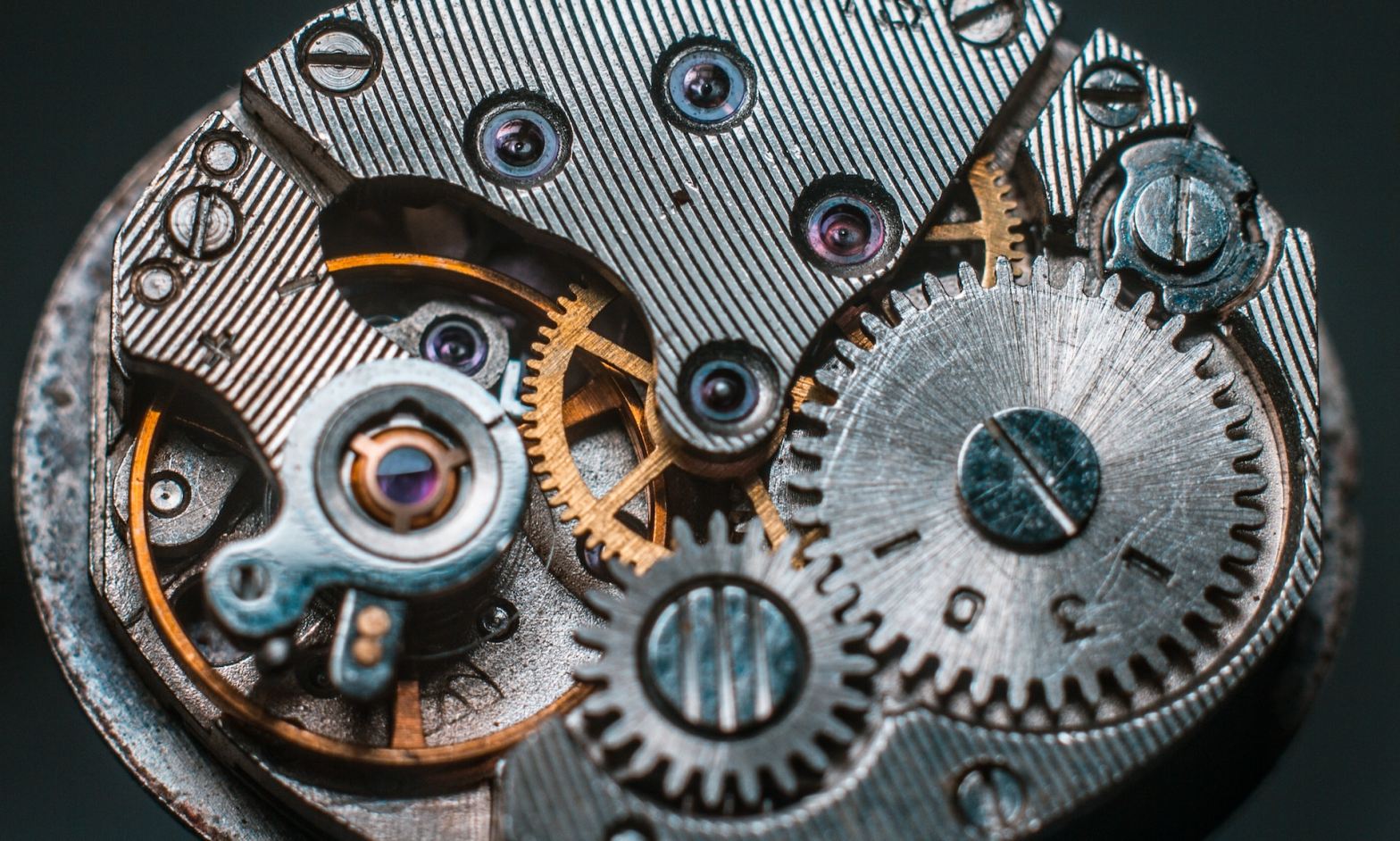

One striking anomaly in such capitals, especially coming from a so-called underdeveloped nation, is that the public clocks work. The hour and the minute hands of the clock provide the rhythms for such a society to function, governing the rhythms of movement as people rush to catch the train, the rhythms of labour as workers rush for to get to work on time, and the rhythms family life as the nature of relationships within a family are governed by the relationship of the members of the family to the economic system. While such rhythms provide great material benefit to the community, they break our relationships to each other, relationships which are meant to provide for the soul. What one finds in such societies is a scourge of loneliness, estranged families, and lack of purpose as one turns their cog in the giant wheel.

Each side of this proverbial coin exhibits glories which bring about human flourishing, as well as well toxins from the Adam’s original sin polluting those glories. Those who have considered migrating from a developed nation to a developing nation or the other way around have considered these trade-offs and weighed them on the balance of their life circumstances. Yet, this isn’t the only way.

In the last pages of the Revelation of John, it paints a beautiful picture of a new and beautiful city coming down from the heavens, creating a solace on earth. It stands in stark contrast to the fallen Babylon, representative of every collective human endeavour to form rhythms of economic order through the subduing of humans into forming its conformant bricks. The new Jerusalem does not need the sun and the moon as its rhythms are formed by God, whose glory and order illuminates the city. It has the economic flourishing of a strong central authority, without the destruction because that authority is God, and He is good. It has social flourishing as the tree planted along the river produces leaves for the healing of the nations. And it’s an everlasting kingdom that will carry the flourishing of its citizens into eternity. Amen! Come, Lord Jesus!

Until then, the church, the gathered citizens of that future kingdom, have the opportunity to provide the world glimpses of that beauty. Yet, this would require us to live as loving dissidents to the outworking of Babylon, wherever we find ourselves. In places where the forces of nature and the thorns and thistles steal human flourishing, the church could be part of building institutions for the common good such as schools and hospitals, following in the footsteps of those who have walked before us. In areas where human relations are destructively mediated by the system, whether that be governmental systems or technological platforms, the church brings people together to forms rhythms of humanity, mediated by the glory of God and the freedom gained by the cross. This glorious and loving freedom would allow us to celebrate together through joys, mourn together through pain, and communally sing together through it all.

Photo by Danil Shostak on Unsplash